Optimizing Postpartum Coverage Extension

By Anoosha Hasan and Allie Atkeson / September 25, 2023

Introduction

The postpartum period, defined as the period after childbirth, is a critical time for maternal and neonatal health and well-being. More than half of pregnancy-related deaths occur in the first year after birth, with 33 percent of pregnancy-related deaths occurring between one week and one year postpartum. There are stark disparities in maternal mortality, with Black women 3.3 times and American Indian/Alaskan Native women 2.5 times more likely to die from a pregnancy-related cause than White women.

Comprehensive postpartum care can address elevated health risks during the postpartum period, including through management of chronic health conditions (e.g., hypertension), as well as treatment of mental health conditions (e.g., postpartum depression), which can impact infant health and well-being. Postpartum care can also include counseling on nutrition, breastfeeding, and other preventive health topics that support maternal and neonatal health. Research shows that coverage after pregnancy facilitates access to care, supporting positive maternal and infant health outcomes after childbirth.

Medicaid plays a significant role in perinatal health coverage as the largest single payer of pregnancy-related services, covering 41 percent of births nationally and the majority of births in several states. Extended postpartum coverage is one strategy states are using to advance goals related to improving postpartum health and reducing maternal mortality and severe morbidity. States are increasingly taking up the option to extend continuous eligibility for pregnancy-related Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) coverage from 60 days to 12 months, a pathway introduced as a five-year temporary option under the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA) and made permanent under the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023.[1] As of September 2023, 37 states and Washington, DC, have extended Medicaid postpartum coverage to 12 months. Most states have extended coverage beyond 60 days postpartum using the ARPA state plan option. Extending Medicaid postpartum coverage for up to 12 months provides states with an option for ensuring continuity of coverage during the period of elevated health risk that follows childbirth.

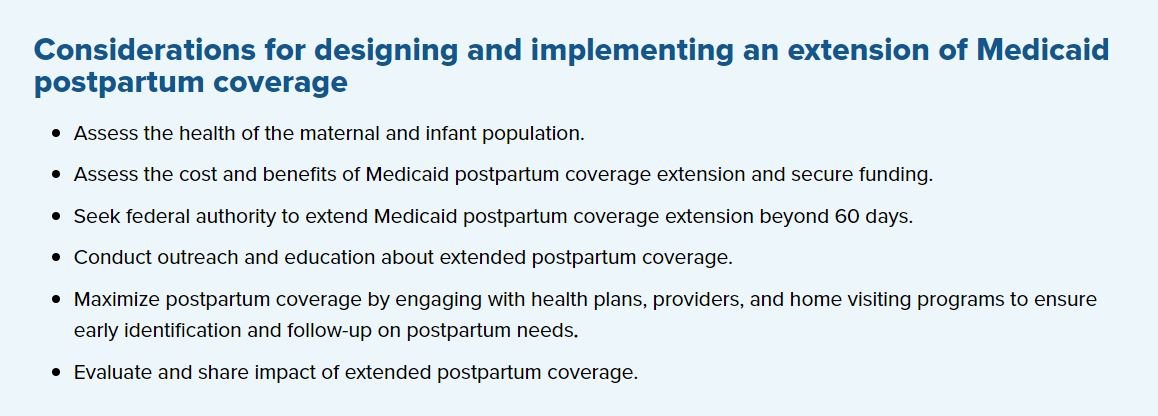

This section of the Operationalizing State Medicaid Policy Levers to Strengthen Perinatal Health Systems toolkit is designed to assist state health officials who are considering, designing, and implementing an extension of Medicaid postpartum coverage. This resource outlines key policy considerations related to extending Medicaid postpartum coverage, highlighting state examples of early adopters of extending postpartum coverage.[2]

Identify sources for measurement and ongoing evaluation, including available maternal and infant health data and reports.

States can analyze both clinical and non-clinical data and reports to assess the health of the maternal and infant population. This can help states identify which subpopulations are disproportionately affected by adverse maternal and infant health outcomes to assess the potential impact of a postpartum coverage extension.

States can review their Maternal Mortality Review Committee (MMRC) reports for recommendations related to a postpartum coverage extension.

Pennsylvania Maternal Mortality Report (2021). The Pennsylvania MMRC recommended safeguarding continuous Medicaid eligibility for individuals during pregnancy and up to one year postpartum.

States can review their Infant Death Review Committee reports to better understand the primary causes of infant deaths and the contributing risk factors. Findings from Infant Death Review Committee reports can help inform action steps to prevent infant deaths and improve health outcomes and may include strategies related to postpartum coverage.

Louisiana Child Death Review Report (2018–2020). The Louisiana State Child Death Review Panel states that maternal health strongly influences infant health and that adequate maternal health insurance coverage and consistent access to quality health care is needed to support infant health. The panel recommends increasing access to family planning services and quality primary care before and between pregnancies to improve maternal health and reduce infant mortality.

States can use data dashboards to review pregnancy-associated mortality data and other measures of perinatal and infant health.

The Missouri Pregnancy-Associated Mortality Review Dashboard (2017–2019) includes information such as timing of death (e.g., during pregnancy or postpartum period), contributing factors (e.g., mental health condition, substance use disorder, obesity), and demographic indicators.

The New York Maternal and Child Health Dashboard (2020) includes several measures of perinatal and infant health, data, and indicators of meeting maternal and child health 2020 objectives.

States can review site-specific, population-based data on maternal attitudes and experiences before, during, and shortly after pregnancy collected by Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), a surveillance project of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and health departments. PRAMS surveillance currently covers about 81 percent of all U.S. births.

The Louisiana State Child Death Review Panel used PRAMS data to augment risk factor findings and prevention recommendations for infant mortality.

Conduct outreach and convene partners, focus groups, and/or interested parties to understand maternal health needs among Medicaid members.

Washington, DC’s Maternal Health Advisory Group advised the Department of Health Care Finance on its expansion of maternal health services and expanded Medicaid postpartum coverage in fiscal year 2022. The advisory group advised on training, public outreach, program support, and other items related to implementation of new maternal health coverage and benefits.

Pennsylvania is developing a statewide maternal health strategic plan that will involve roundtable discussions and events with pregnant and postpartum people to provide the departments of Human Services, Health, and Drug and Alcohol programs with qualitative data on maternal health needs to advance health equity and improve services.

Tennessee’s Maternal Health Task Force includes representation from TennCare (Tennessee’s Medicaid agency), hospitals, patient support advocacy groups, doulas, certified nurse-midwives, and others to develop and implement strategies that align with the maternal mortality review committee recommendations.

States are using a variety of approaches to understand the costs and benefits for extending postpartum coverage. States may assess the utilization and costs for postpartum services and estimate the baseline annual cost for postpartum coverage extension.

The Iowa Department of Health Services submitted a report to the Iowa General Assembly in December 2022 on postpartum coverage available to recipients of pregnancy-related Medicaid coverage. The report includes the number of recipients of postpartum services, the services utilized, and the costs for such services from January 1, 2020, through June 30, 2022.

For states that have expanded Medicaid in the adult group category, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) offers the opportunity to use a “proxy methodology” to receive the enhanced expansion match for individuals covered under the extended postpartum coverage state plan option (made possible by ARPA) who would otherwise be eligible for coverage in the Medicaid expansion group. This ensures that states do not lose the enhanced expansion match for this postpartum population, which could otherwise deter states from taking up the option

States can submit a SPA for federal approval to adopt the option to permanently extend postpartum coverage to 12 months.

States that take up the state plan option receive federal matching funds at the per-capita based federal medical assistance percentage. The state plan option offers full Medicaid benefits for nearly all Medicaid-enrolled postpartum people. When a state elects the state plan option in Medicaid, it must also do so for targeted, low-income pregnant people enrolled in CHIP. For example:

Hawaii’s approved SPA to extend Medicaid postpartum coverage to 12 months went into effect in April 2022.

South Carolina’s approved SPA to extend Medicaid postpartum coverage to 12 months went into effective in April 2022.

States can request to extend Medicaid or CHIP postpartum coverage through a Section 1115 demonstration waiver.

States that pursue a Section 1115 demonstration waiver to extend Medicaid or CHIP postpartum coverage may do so to extend coverage for certain subpopulations and services and possibly for shorter lengths of time (e.g., six months). States must demonstrate that federal costs would not be increased under the waiver. For example:

Florida’s waiver extends postpartum coverage for Medicaid members up to 191 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) and CHIP members with family income from 134–191 percent of FPL. The waiver extends coverage for postpartum people through 12 months after delivery.

Virginia’s approved waiver to extend FAMIS MOMS Medicaid and CHIP coverage to 12 months postpartum is effective through June 2029.

Educate Medicaid members and providers about the period of coverage and services available as a result of the postpartum coverage extension.

CMS has provided guidance to states on educating beneficiaries about the availability of extended postpartum coverage, including strategies to raise awareness of extended postpartum coverage and conduct member and provider outreach and education.

In some states, members may be eligible for an extended period of coverage and a broader range of Medicaid benefits, particularly in those states that have not expanded Medicaid to cover low-income adults.

For example, prior to the ARPA postpartum coverage extension option, pregnant people in North Carolina qualified for Medicaid for Pregnant Women, a limited maternity-focused set of benefits. Since the state expanded postpartum coverage in 2022, pregnant and postpartum people in North Carolina are now eligible for full Medicaid benefits. As of September 2023, North Carolina is awaiting budget authority to begin implementation of Medicaid expansion.

North Carolina created a landing page on the state Medicaid agency website focused on the postpartum coverage extension. The page includes fliers in English and Spanish that identify full Medicaid benefits available during the postpartum period in addition to a resource document and frequently asked questions (FAQ) page for providers.

Alabama released an alert to Medicaid providers to notify them of the extended Medicaid postpartum coverage.

Louisiana sent a memorandum to Medicaid managed care organizations asking them to make Medicaid providers aware of the extended postpartum coverage.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ (ACOG) Presidential Task Force on Redefining the Postpartum Visit released a committee opinion on optimizing postpartum care, which was endorsed by the American College of Nurse-Midwives, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, and others. The committee opinion recommends that all postpartum individuals have contact with their obstetric care provider within the first three weeks postpartum and a comprehensive postpartum visit no later than 12 weeks after birth. In addition to these recommendations, the committee opinion also outlines aspects of physical, social, and psychological well-being as critical components to postpartum care.

Recognizing that the timing of the comprehensive postpartum visit should be individualized and women-centered, ACOG and other maternal health organizations have proposed extending the traditional six-week postpartum visit to a 12-week process that includes a blood pressure check at three to 10 days postpartum, ongoing follow-up from the primary maternal care provider, and eventual transition to well-woman care. Extension of Medicaid postpartum coverage aligns with this clinical guidance by ensuring women have continuous coverage past six weeks and up to a year postpartum. To optimize postpartum coverage extension, states can engage home visiting programs, providers, and health plans in efforts to maximize the impact of postpartum care.

Consider covering many individual component services of home visiting programs through existing Medicaid authorities to optimize postpartum care.

Medicaid members in Maryland who are pregnant or are up to three months postpartum are eligible to receive home visiting services that include educating members about healthy parenting skills.

In South Carolina, the Postpartum Newborn Home Visit provides one- to two-hour visits from a nurse that are covered by some Medicaid insurance plans. These visits connect new families with health care, social services, and education on topics such as nutrition and sleep.

Encourage Medicaid providers and/or plans to improve postpartum care for beneficiaries.

To identify disparities in access to care and health outcomes and continue developing initiatives to improve maternal health equity, states can mandate or recommend quality measure tracking and reporting (e.g., the Postpartum Care measure from CMS’ Maternity Core Set).

States can also require managed care organizations to implement performance improvement projects designed to improve care for pregnant and postpartum people.

Iowa requires its managed care organizations to conduct a performance improvement project related to timeliness of postpartum care. The performance indicator for this performance improvement project assessed the rate at which women who delivered a live birth in the measurement period had a postpartum care visit on or between seven and 84 days after delivery.

As a new policy option, it is important to evaluate the impact of extended postpartum coverage on maternal and infant health outcomes, and states have a variety of options:

Analyze data from the previous public health emergency’s continuous coverage requirement.

The previous Medicaid continuous enrollment requirement associated with the COVID-19 public health emergency created a natural experiment to determine the impact of continuous coverage during the postpartum period. One health maintenance organization in Texas found that women continuously enrolled past 60 days postpartum utilized 10 times as many contraceptive services and 37 percent fewer services for subsequent pregnancies during their first year postpartum. Postpartum women with continuous coverage also used three times as many behavioral and mental health services and substance use disorder services and twice as many outpatient services.

Conduct 1115 waiver demonstration evaluations.

States that extended Medicaid postpartum coverage through an 1115 demonstration waiver must submit initial evaluation plans as a part of their waiver approval and use.

Virginia’s 1115 waiver evaluation will use eligibility and enrollment, utilization, claims, and MCO data to assess the impact of extending Medicaid and CHIP postpartum coverage to 12. Virginia seeks to:

Promote continuous coverage and continuity of care for women in the postpartum period.

Increase access to medical and behavioral health services and treatments for women in the postpartum period.

Improve health and address health-related social needs for postpartum Medicaid and CHIP enrolled women.

Improve health access and health outcomes for infants of postpartum Medicaid and CHIP enrolled women.

Advance health equity by reducing racial/ethnic and other disparities in maternal coverage, access, and health outcomes as well as infant health outcomes among postpartum Medicaid and CHIP enrolled women and their infants.

Leverage the Maternity Core Set.

The CMS Maternity Core Set allows states to track the quality of care members receive. Beginning in 2024, states will be required to report the behavioral health measures in the Adult Core Set and the full Child Core Set, which includes six of the Maternity Core Set measures. Stratifying quality measures by race and ethnicity can help states identify areas to reduce health inequities.

Virginia’s Medicaid managed care dashboard includes two perinatal health measures: timeliness of prenatal care and receipt of postpartum care seven to 84 days after delivery.