Medicaid Per Capita Cap Would Harm Millions of People by Forcing Deep Cuts and Shifting Costs to States

By Gideon Lukens and Elizabeth Zhang / January 7, 2025

Recent proposals from Republican congressional leaders and a conservative think tank would impose a per capita cap on federal Medicaid funding or, similarly, turn Medicaid into a block grant.[1] These proposals would dramatically change Medicaid’s funding structure, deeply cut federal funding, and shift costs and financial risks to states. Faced with large and growing reductions in federal funding, states would cut eligibility and benefits, leaving millions of people without health coverage and access to needed care.

Many of those losing Medicaid coverage would be left unable to afford life-saving medications, treatment to manage chronic conditions like cardiovascular disease and liver disease, and care for acute illnesses. People with cancer would be diagnosed at later stages and face a higher likelihood of death, and families would have more medical debt and less financial security. A large body of research shows that Medicaid improves health outcomes, prevents premature deaths, and reduces medical debt and the likelihood of catastrophic medical costs.[2]

Before resurrecting harmful per capita cap proposals, policymakers should consider how similar past proposals would have impacted states’ budgets and thus their ability to support Medicaid enrollees. This paper presents a case study with historical data to illustrate the impact on different states had Congress implemented a per capita cap in 2018; nearly every state examined would have exceeded its cap — and thus lost substantial federal funding — in one or more of the following four years.

Per Capita Cap Designed to Cut Medicaid by Growing Amounts Over Time

The federal government pays a fixed share of states’ Medicaid costs, which gives them the predictability they need to run their programs because the amount they receive is based on actual costs incurred.[3] Under a per capita cap, the federal government would instead pay states no more than a fixed amount of funding per enrollee, leaving states responsible for all remaining costs.

A per capita cap is designed to cut federal Medicaid funding by setting spending limits well below what would be needed to keep pace with rising health care costs. Each state would be assigned its own initial per capita cap based on the state’s current or historical spending; this amount would be set to increase each year at a rate below the growth in per capita health care spending. Thus, the cuts would increase over time. Even a proposal with modest annual cuts in the initial years would produce large (and ever-growing) annual cuts in later years. As the annual cuts grow, the cumulative cut to federal funding would grow increasingly rapidly. (See Figure 1).

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated various scenarios by which Congress could cap Medicaid spending and found that a per enrollee cap would cut federal spending by between $588 billion and $893 billion over nine years, depending on the annual rate at which federal funding would be permitted to grow under the cap. An overall cap (also known as a block grant) functions similarly to a per capita cap, except states would receive a fixed dollar amount that wouldn’t adjust for changes in enrollment. An overall cap would cut federal spending by between $459 billion and $742 billion.[4]

CBO estimates that federal funding reductions of this magnitude would cause states to cut Medicaid coverage, including some states dropping the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid expansion, along with other cost-cutting actions such as reducing Medicaid benefits and provider payments. CBO estimates that about half of the people losing Medicaid coverage would become uninsured. In a previous analysis, CBO noted that under a per capita cap or overall cap, households could face significant increases in medical debt and bankruptcies.[5]

Federal Funding Cuts Would Be Unpredictable and Beyond States’ Control

The federal funding cuts under a per capita cap would be highly unpredictable and largely beyond states’ control, reflecting factors such as rising medical care prices, population aging and other demographic changes, and potentially natural disasters and epidemics. [6]

Underlying drivers of growth in per person medical costs include developments in medical technology such as new medicines, devices, and procedures, along with changes in health care utilization and medical practice patterns.[7] Changes in these factors are impossible to predict and extremely difficult for states to control, and their impacts could vary greatly among states. For example, a breakthrough procedure or drug for patients with cancer or Alzheimer’s disease could lead to an unexpected increase in medical care costs, the size of which would vary across states due to state differences in disease burdens and age distributions.

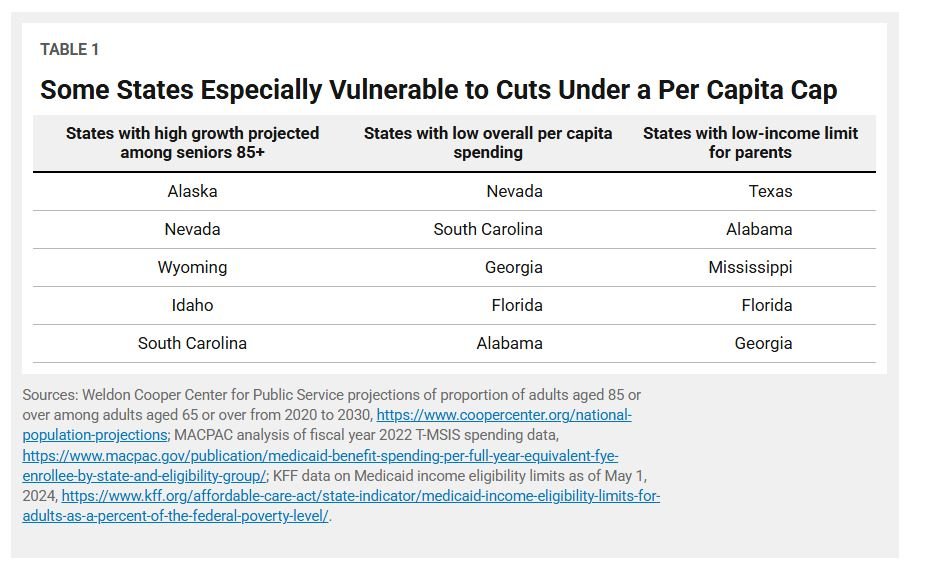

Medical cost growth also fluctuates based on changes in demographics and health conditions. In general, the bulk of Medicaid spending is needed to care for a relatively small subset of patients with significant health care needs, so fluctuations in the number of these high-cost patients could have outsized cost impacts.[8] For example, Medicaid enrollees who use Medicaid long-term services and supports (LTSS) due to chronic illness or disability have health care costs around nine times higher than other enrollees.[9] Adults aged 85 and older are more likely to use LTSS,[10] so the states expected to have growing shares of older adults are more likely to substantially exceed a per capita cap for the aged 65 or over eligibility group.

Moreover, because a state’s initial funding under a per capita cap is based on current or historical per person costs, a per capita cap would lock in existing differences in spending across states.[11] States with lower initial per enrollee costs would continue to receive less federal funding than states with higher initial costs. And because states with low costs tend to experience faster cost growth than states with high costs, states with lower initial costs would likely face bigger cuts.[12]

A per capita cap may also disproportionately harm states with more restrictive eligibility and benefits policies, lower provider payments, and existing cost-containment strategies such as expansive use of managed care and delivery system reforms. These states have less room to further lower costs to stay within per capita caps, forcing them to make the most harmful cuts earlier and to a deeper extent. (See Table 1.)

Block grants suffer from the same flaws as per capita caps and add another layer of uncertainty because federal funding wouldn’t automatically adjust for changes in enrollment growth.[13] Enrollment growth hinges on factors such as recessions, demographic changes, and shifts in the income distribution, which are often difficult to predict and vary among states.

Case Study: What if a Per Capita Cap Had Been Implemented in 2018?

The following case study uses historical data to illustrate the impact on different states if a per capita cap had been implemented in 2018. It does not reflect a specific proposal but rather policies similar to multiple proposals, including the American Health Care Act (AHCA), which passed the House in April 2017,[14] and the Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA), which was proposed in the Senate in June 2017.[15]

n line with proposals such as the AHCA and BCRA, which assigned each state a separate cap for each eligibility group, our examples include separate caps for enrollees with disabilities, adults aged 65 or older, children, adults eligible through the ACA Medicaid expansion, and other adults not eligible through the ACA expansion. Per capita caps could instead assign a single cap for all Medicaid enrollees, regardless of eligibility group, but this would incentivize states to aggressively limit spending for populations with greater health care costs (and needs), such as people with disabilities and seniors.

We use data from fiscal years 2018 to 2022,[16] the longest period for which comparable data are available, and exclude nine states and the District of Columbia due to data quality issues, restricting our analysis to the remaining 41 states.[17] We assume that baseline spending per person is based on full-benefit spending in each eligibility group in fiscal year 2018, and that the caps adjust each year according to a pre-established growth factor.

Almost All States Would Have Exceeded Per Capita Cap

On average across the U.S., Medicaid costs per person rose roughly in line with historical trends in 2019 and 2020 and then grew more slowly in 2021 and 2022, in part due to the pandemic-related continuous coverage provision.[18] Yet many states still would have exceeded the caps during the slower growth period in 2021 and 2022 due to faster initial growth in spending in 2019 and 2020.

The following examples assume that per capita caps are set to grow by the medical consumer price index (CPI-M) for all eligibility groups. (See box, “Per Capita Caps Designed to Grow More Slowly Than Expected Costs.”) Under the CPI-M, almost all states would have exceeded the caps in at least one year from 2019 to 2022. (See Figure 2 below.)

For enrollees with disabilities, 38 of the 41 states would have exceeded the cap in at least one year, and 23 would have exceeded the cap in all years. For example:

Iowa would have exceeded the cap in all years: by 7 percent in 2019, 8 percent in 2020, 3 percent in 2021, and 11 percent in 2022.

Pennsylvania would have exceeded the cap by 12 percent in 2020, 13 percent in 2021, and 16 percent in 2022.

For adults aged 65 or older, 29 of the 41 states would have exceeded the cap in at least one year, and eight would have exceeded the cap in all years. For example:

North Carolina would have exceeded the cap in all years: by 1 percent in 2019, 5 percent in 2020, 22 percent in 2021, and 19 percent in 2022.

Louisiana would have exceeded the cap by 15 percent in 2019.

For children, 33 of the 41 states would have exceeded the cap in at least one year, and 14 would have exceeded the cap in all years. For example:

Idaho would have exceeded the cap in all years: by 15 percent in 2019, 16 percent in 2020 and 2021, and 6 percent in 2022.

Maine would have exceeded the cap by 8 percent in 2020 and 2 percent in 2021.

For non-expansion adults, 35 of the 41 states would have exceeded the cap in at least one year, and 12 would have exceeded the cap in all years.

Arizona would have exceeded the cap in all years: by 3 percent in 2019, 2 percent in 2020, 15 percent in 2021, and 18 percent in 2022.

New Hampshire would have exceeded the cap by 10 percent in 2020 and 3 percent in 2021.

For expansion adults, 19 of the 25 states without data quality issues that had expanded Medicaid before 2018 would have exceeded the cap in at least one year, and 11 would have exceeded the cap all years.

New Jersey would have exceeded the cap in all years: by 8 percent in 2019, 11 percent in 2020, 13 percent in 2021, and 12 percent in 2022.

California would have exceeded the cap by 6 percent in 2019 and 10 percent in 2022.

The AHCA and BCRA allowed slightly higher growth in the caps for enrollees with disabilities and enrollees aged 65 or older. They set a growth rate of the CPI-M plus one percentage point (CPI-M + 1) for those two groups, while keeping the CPI-M for adults and children. But even with this slightly higher growth rate, most states still would have exceeded the caps for these groups in at least one year. (See Figure 2.)

For enrollees with disabilities, 36 of the 41 states would have exceeded the cap in at least one year, and 18 would have exceeded the cap in all years. For example:

Iowa would have exceeded the cap in all years: by 6 percent in 2019 and 2020, less than 1 percent in 2021, and 7 percent in 2022.

Pennsylvania would have exceeded the cap by 9 percent in 2020, 10 percent in 2021, and 12 percent in 2022.

For adults aged 65 or older, 28 of the 41 states would have exceeded the cap in at least one year, and six would have exceeded the cap in all years.

New Jersey would have exceeded the cap in all years: by 8 percent in 2019, 4 percent in 2020 and 2021, and 11 percent in 2023.

North Carolina would have exceeded the cap by 10 percent in 2020, 18 percent in 2021, and 14 percent in 2022.

Louisiana would have exceeded the cap by 14 percent in 2019.

Per Capita Caps Would Have Substantially Increased State Costs

With these caps in place, states would have lost substantial shares of federal funding and, as a result, faced higher costs. Even if states were allowed to “cross-subsidize” — that is, to make up for spending over the cap in one eligibility category by spending under the cap in another, as permitted under the ACHA and BCRA — 35 of the 41 states would have faced higher costs in one or more years from 2019 to 2022.[19] (This analysis assumes annual growth factors combining the CPI-M and CPI-M + 1, as described above.) For example:

Ohio would have exceeded the cap in four eligibility categories. As a result, it would have lost $190 million in federal funding in 2019, or 3 percent of its total state-funded Medicaid benefit spending. These additional costs would have grown each year. In 2022, Ohio would have lost nearly $2 billion in federal funding, or 26 percent of state-funded Medicaid benefit spending.

Minnesota and many of the other states that fell below the cap in 2022 would nevertheless have faced cuts in earlier years. This is because per capita caps present a one-sided arrangement where states can only lose: in years where they exceed the cap, states experience cuts in federal funding, but they gain no additional funding in years where they fall below the cap.[20] Over time, even if a state’s per capita costs grow more slowly than the growth rate of the cap on average, the state could still experience cuts.

As discussed above, states with lower baseline per capita spending are more vulnerable to cuts under a per capita cap. The five states in our analysis that would have faced cost increases exceeding 25 percent of their total state-funded benefit expenditures in 2022 — Arizona, California, New Mexico, Ohio, and Texas — all had overall per capita spending well below the national average in 2018.

If cross-subsidization were prohibited, cost shifts to states would be even more extreme; every state would face costs equal to or — more often — greater than if cross-subsidization were allowed. As a result, 40 of the 41 states in our analysis would have had to bear additional costs due to a per capita cap between 2019 and 2022. For example:

Michigan’s additional cost in 2022 would have been $1 billion, compared to $600 million if cross-subsidization were allowed.

Idaho would have faced an additional $150 million in costs, or 12 percent of total state-funded Medicaid benefit spending, in 2021 and 2022 combined. If cross-subsidization were allowed, Idaho would have fallen below the cap in both years.

Within just those four years, almost all states would have faced substantial cuts in federal funding under a per capita cap, even as spending per person slowed in the latter two years. This is because the design of per capita caps can expose states to cuts even if spending falls below caps for some eligibility groups, and even if spending growth falls below the cap on average over time. And as the caps would be permanent, the size of the cuts and the number of states affected would continue growing over time. These losses in federal support would impose significant strain on states and put millions of people at risk of losing benefits and coverage.

Per Capita Cap Would Force States to Cut Benefits and Eligibility

A per capita cap or block grant, by imposing increasingly draconian cuts in federal Medicaid funding over time, would force states to cut some combination of benefits, eligibility, and payment rates for managed care plans and health care providers. Most likely, states would make cuts in all three areas, putting tens of millions of older people, people with disabilities, children, and families in serious jeopardy of becoming uninsured, losing access to the care they need, experiencing worse health outcomes, and accumulating medical debt.

States could cut eligibility for groups such as children in families with income above mandatory eligibility group levels; pregnant women with incomes over statutory minimums; and some people with disabilities and adults aged 65 or older whom states currently cover but aren’t required to. States that haven’t yet implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion would be less likely to do so, and other states could consider dropping expansion.

Many states could also cut benefits that they provide but are not required to, such as vision, dental, and home- and community-based services. And states could cut provider payment rates, which are already well below the rates that providers get from private health insurance or Medicare. This could cause some providers to refuse to accept Medicaid patients, diminishing their access to needed care.

People of color disproportionately use Medicaid for their health coverage, a result of racially discriminatory systems that create barriers to wealth-building, opportunity, and jobs with employer-provided health insurance. A per capita cap or block grant and the resulting cuts would deepen racial and ethnic inequities in coverage, access to health services, and health care quality.[21] People with disabilities also could be particularly vulnerable to losing coverage and benefits since their health care needs cost more, accounting for 11 percent of Medicaid enrollees but 30 percent of Medicaid benefit spending.[22] In addition, states are not required to provide many of the home- and community-based services that people with disabilities rely on, like personal care services or adult day care.

And in stark contrast to Medicaid’s current financing structure, which enables the program to respond automatically to changes in need, a per capita cap or block grant would result in larger funding shortfalls during a downturn, when demand for Medicaid tends to increase.[23] Under a per capita cap, states would get additional funding as the number of enrollees increased, but if the caps were set at an insufficient level, the state’s funding shortfall would grow as more people enrolled. Under a block grant, the funding shortfall would be even worse since federal funding wouldn’t change in response to enrollment increases.

In short, recent proposals for a per capita cap or block grant would cause people to lose health coverage and benefits, shift costs and risks to states, and destabilize health care providers. The federal funding cuts to states would be large and unpredictable. Restructuring Medicaid’s financing would also make the program highly vulnerable to future cuts, as it would impose a funding formula that could be easily ratcheted down further — for example, by setting the cap or its growth rate even lower. Policymakers should reject proposals for per capita caps and block grants and instead retain the current federal-state financial partnership.