Health Cost and Affordability Policy Issues and Trends to Watch in 2024

By Krutika Amin, Emma Wager, Zachary Levinson, Juliette Cubanski and Cynthia Cox , KFF / January 24, 2024

While issues of health care costs and affordability may not be at the forefront of this year’s election, they remain a major concern among the public. Health spending in the United States is projected to grow by 5% between 2023 and 2024, to a total of $4.9 trillion. Here are key health costs and affordability policy issues and trends to watch in 2024.

Will policymakers pass site-neutral payment reforms?

Payments for outpatient services frequently vary depending on the type of setting where they’re provided. For example, reimbursement rates are often higher for a given service when provided in a hospital outpatient department versus a freestanding physician office, even though in many of these circumstances care may be safe and appropriate in either setting. Policymakers and payers have expressed interest in aligning payments across care settings through “site-neutral payment reforms.” Through legislation and rulemaking, Medicare has aligned payments for office visits across freestanding physician offices and off-campus hospital outpatient departments—which often resemble physician offices—as well as for other services for relatively new off-campus facilities. The U.S. House of Representatives passed a bill in December 2023 (HR 5378) that would align Medicare payments for drugs administered in off-campus hospital outpatient departments and freestanding physician offices, which the CBO estimates would save $3.7 billion over 10 years. Other proposals, such as aligning payments for both on- and off-campus hospital outpatient departments with payments for ambulatory surgical centers or physician offices for certain services, could lead to much larger savings. Policymakers have also explored reforms intended to address outpatient facility fees—which are on top of professional fees for a given service and can add substantially to the total bill—charged by hospitals and other institutional providers in commercial markets. In addition to directly lowering costs for payers and individuals, site-neutral payment reform could reduce the incentive for hospitals to buy up physician practices, a practice which has been associated with higher commercial prices. Nonetheless, hospitals and other opponents have argued that there are differences in the patients that hospitals care for, the services they provide, and their cost structure that justify higher payment rates.

Will price transparency requirements drive down costs?

Federal price transparency requirements exist to allow consumers to compare prices across hospitals and providers. Health plans and employers may also be able to use some of the price transparency data to negotiate lower rates. There is bipartisan interest in price transparency and recently the U.S. House passed a bill (HR 5378) codifying existing price transparency regulations and extending the requirements to diagnostic labs, imaging services, and surgical centers. However, the Congressional Budget Office expects price transparency to have very little impact on health sector prices. State-level studies suggest price transparency can result in unintended consequences if it results in competitors demanding higher prices. Additionally, few consumers use these tools to shop for care, and those who do try to price-shop may find that timely or convenient alternatives are not available. For price transparency to make a meaningful difference in costs for consumers, targeted approaches with a more limited set of services that consumers truly shop for may be most effective. Price transparency is a largely bipartisan issue, so federal solutions to these issues are not impossible in 2024.

How will prescription drug pricing policies affect health spending and affordability?

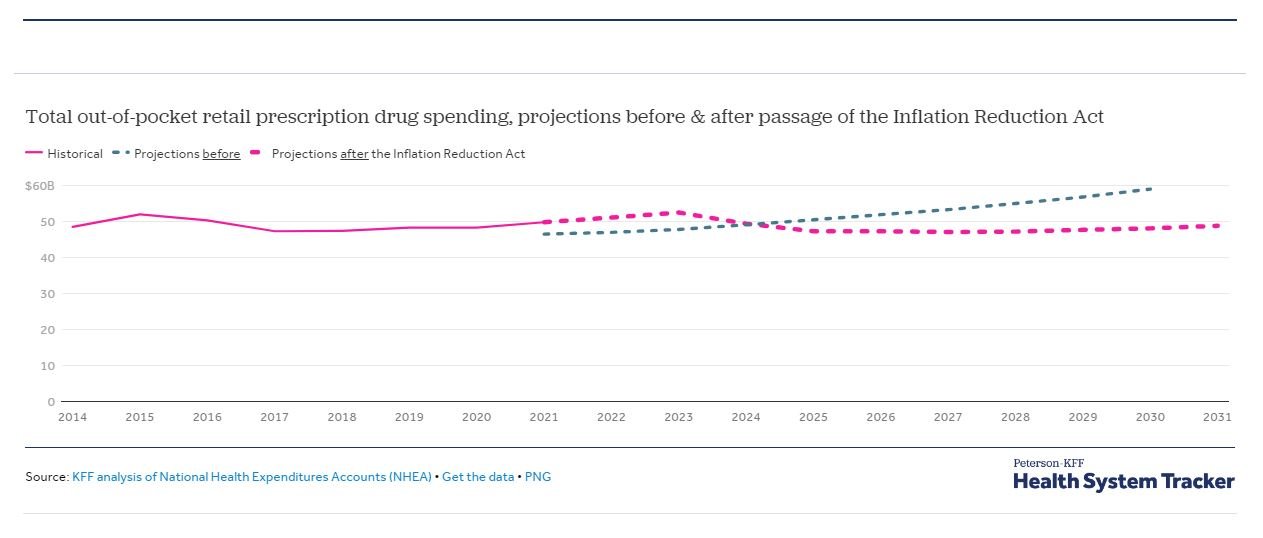

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 included numerous provisions aimed at prescription drug spending in the Medicare program, including capping insulin cost-sharing to $35 a month (starting 2023), requiring pharmaceutical manufacturers to pay rebates if prices exceed inflation (starting 2023), capping Medicare Part D out-of-pocket drug spending by eliminating the 5% coinsurance requirement for catastrophic coverage (in 2024) and adding a hard cap at $2,000 (starting in 2025) , and requiring the federal government to negotiate prices for some high-spend drugs (negotiated prices take effect in 2026). Before the Inflation Reduction Act, CMS projected aggregate out-of-pocket retail prescription drug spending to increase steadily throughout the 2020s. CMS now expects out-of-pocket drug spending to peak in 2023 at $52.5 billion and decline thereafter through 2027 as provisions take effect. By 2030, total out-of-pocket spending on retail prescription drugs is projected to be $48.1 billion, 18.5% lower than the $59.0 billion projected previously. While none of these provisions cover privately insured people, the effects of some of the Medicare drug price regulations may spill over to the private market, though the effects are highly uncertain, including whether manufacturers might attempt to make up for lost revenue in Medicare by raising prices for other payers.

What new policies might affect PBMs, the so-called prescription drug middlemen?

Many proposals have sought to increase transparency in pharmaceutical benefit manager (PBM) operations, for example, by requiring the disclosure of rebates and discounts negotiated with pharmaceutical manufacturers. Transparency measures are intended to provide more clarity on the pricing dynamics within the pharmaceutical supply chain. Other proposals are aimed at regulating how the PBM market operates; for example, banning PBMs from charging health plans more for a drug than the amount they reimburse pharmacies (a practice known as “spread pricing”), requiring PBMs to pass on all rebates received from manufacturers to health plans, or limiting compensation to PBMs based on a flat-dollar service fee, which would dampen current incentives around rebates based on high drug prices. Additional efforts have focused on market dynamics and competition among PBMs. For example, the Federal Trade Commission recently has deepened its inquiry into business practices of PBMs and rebate aggregators. These efforts may shed light on the impact of rebates and discounts on health care costs in the future. The House passed legislation in December 2023 with several provisions targeting PBMs, but it is unclear which provisions could become law as part of broader health care or spending-related legislation this year.

How will new drugs and therapies impact health spending and outcomes?

Obesity, one of the most common health conditions in the U.S., saw new treatments enter the spotlight in 2023 – most notably, the use of semaglutide and tirzepatide drugs for weight loss. While the coverage of these drugs is still being debated by many health plans and the long-term effects have yet to be determined, they have become an extremely popular option for patients and shown promise in clinical trials. In 2024, more Americans will want access to these medications, and spending on them will continue to increase. Notably, however, Medicare does not cover drugs used for weight loss, so it remains an open question whether people with Medicare will enjoy broad access to these medications as long as this coverage restriction remains in place. At the same time, lifting Medicare’s coverage prohibition would lead to substantially higher Medicare spending, given the high price of these medications and expected demand. It remains to be seen if medication for obesity can lead to significant population-level health improvements and potentially reduce spending on care for related diseases, such as hypertension and diabetes. Private insurers and employers are figuring out whether and how to cover these new drugs—coverage and cost-sharing will likely vary by health plan. Additionally, new high-cost cell and gene therapies show potential for improving health outcomes and may also affect total health spending; coverage for new treatments will also likely vary by payers and health plans.

How will expansion of virtual care affect costs, access, and affordability?

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, health care visits via telehealth increased substantially. Regulators and payers began reimbursing for virtual care, expanding clinician participation and patient access. Medicare removed restrictions on the use of telehealth that were in place prior to the pandemic, broadening access to telehealth services for beneficiaries in both urban and rural areas, at home and in other settings, using audio-visual and audio-only technologies, and from a wide range of health care providers. Expanded access under Medicare is scheduled to expire at the end of 2024, though there are proposals to make these provisions permanent. Regulators also expanded clinicians’ ability to practice and prescribe over virtual consultations. Particularly when in-person care may not be safe, like during the pandemic, or where there are limits to accessing providers in-person, virtual care provides a convenient alternative. Additionally, new state-level restrictions on access to certain services, such as abortion drugs, have sparked interest in prescribing across state lines, which is currently heavily restricted. How telehealth and virtual care affect care coordination, quality of care, health outcomes, and overall costs, remains to be seen in 2024.

Will state cost control measures succeed at curbing spending?

Several states have introduced measures to curb health cost growth. States’ experimentation with health care cost controls could have a snowball effect if other states take up similar measures. Programs such as those in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Montana were piloted in the 2010s and their long-term impact is beginning to take shape. The Biden Administration has made funds available for states planning multi-payer hospital global budgets or cost control strategies through the AHEAD model. However, there are some limits on the extent to which states can address drivers of health spending. For example, states are the primary regulators of providers, but can only regulate fully-insured private health insurance plans, which cover just one-third of workers nationally. While there is not a singular national health care cost control strategy, states’ efforts could influence federal policy makers. In 2024, states with cost containment efforts are likely to put effort into demonstrating their effectiveness, and states without these programs may consider adding them.

What effect will recent surprise billing protections have on private insurance premiums?

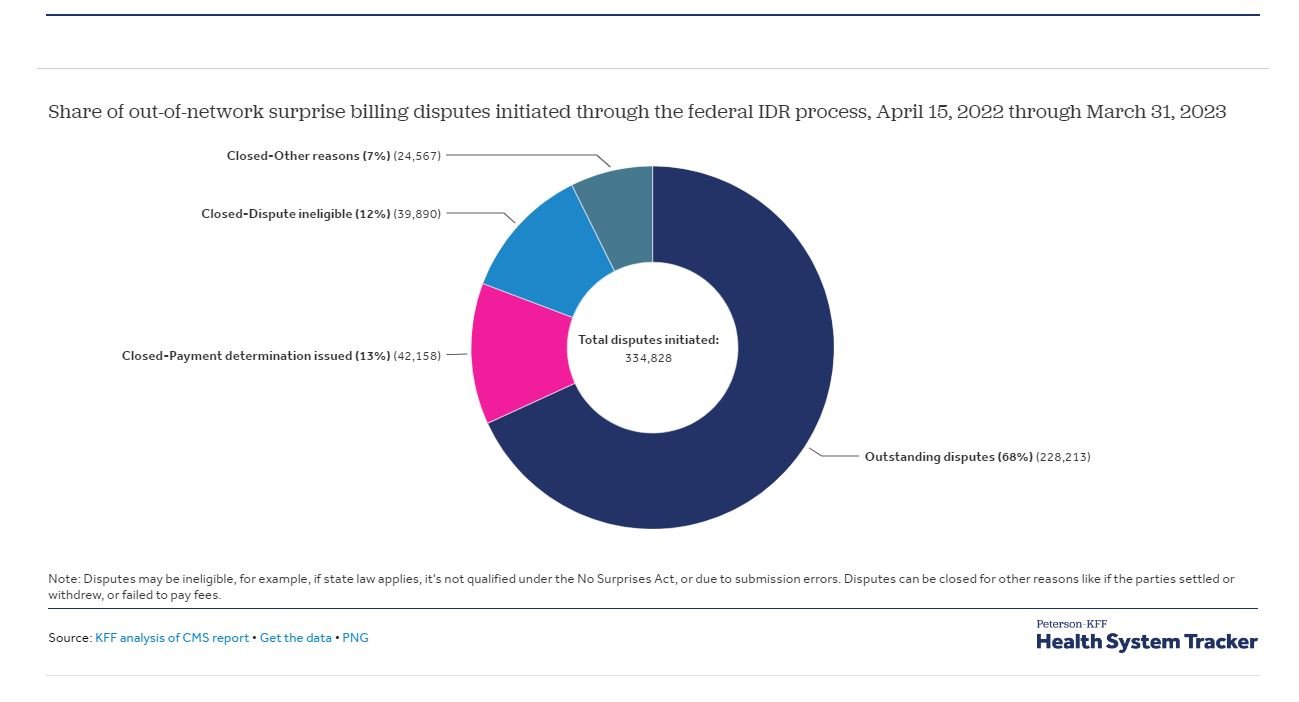

Among privately insured patients, about 1 in 5 emergency room visits and between 9% and 16% of in-network hospitalizations for non-emergency care were previously at risk of surprise bills from out-of-network providers. Congress passed a bill at the end of 2021 prohibiting most surprise bills. For out-of-network services and items covered under the law, plans and providers are no longer allowed to send patients surprise, out-of-network balance bills. How much out-of-network providers are paid is actively being disputed by provider groups in several legal challenges. Outcomes of these challenges will affect payments to providers and health insurance premiums.

Which policies might address out-of-pocket health care costs and consumer medical debt?

The uninsured rate has decreased to a historic low as a result of continuous Medicaid enrollment during the COVID pandemic and expanded subsidies through the Affordable Care Act Marketplaces during the Biden Administration. However, affordability issues persist among people with health insurance. Many people don’t have enough savings to pay for typical deductibles and out-of-pocket maximums. Additionally, millions of Medicaid enrollees have been disenrolled, which is likely to increase the uninsured rate. With higher uninsurance rates, health care affordability issues may increase. Medical debt also remains a significant issue in the U.S., including among people with health insurance. The Consumer Finance Protection Bureau is planning to require credit reporting agencies to remove medical debt from credit reports, as well as cracking down on collection practices that either skip informing patients of outstanding medical bills or put undue pressure on consumers for payments. These measures will free up credit for living expenses. However, unexpected and large health care bills will still occur, particularly for people with significant health care needs and lower income. Some states have similarly acted to remove medical debt from consumers’ credit reports. States and local municipalities have also taken action to buy their residents’ medical debt, in part with remaining COVID relief funds. While these efforts help some consumers, they don’t change the root cause of medical debt – high health care costs and underinsurance.

How will shifts to value-based payment impact health care costs?

For over a decade, there has been significant effort to shift from fee-for-service payment models to value-based payment or pay-for-performance models. The intention is to shift some of the cost risk from payers to providers, and engage providers in improving quality while lowering costs. These payment models vary in structure. Some pay for a bundle of services or on a capitated per enrollee basis, adjusted for case-mix. Others adjust a portion of payments based on various quality and patient care measures. At least a third of provider payments across Medicare, Medicaid, and commercial payers are now based on quality- or value-based models. While some of Medicare’s value-based payment models have demonstrated cost savings, a majority have resulted in increased costs with little to no change in quality. Some quality-based payment models (for example, Medicare’s value-based payment program for clinicians) have been criticized for increasing administrative burden and costs on providers, which may reduce physicians’ incentives to participate. According to CBO, the activities of Medicare’s innovation center (CMMI) increased federal spending by $5.4 billion from 2011 to 2020, which CBO attributes in part to the mixed success of many models at generating sufficient savings to offset their high upfront costs. According to CBO, the voluntary nature of most CMMI models means that providers may self-select into models where they expect gains or not participate where they expect losses. CMS is looking at whether to require participation in more models. Even in the absence of savings, a review of select CMMI models provides evidence of improvements in care coordination, team-based care, and other care delivery changes. CBO’s report and generally disappointing cost savings so far could shift how policymakers and payers move forward with value-based payment models in the future.

What actions will antitrust agencies take to address consolidation in health care markets?

Consolidation in the health care sector can result in higher costs. For example, a substantial body of evidence shows that consolidation in provider markets has led to higher prices without clear evidence of improvements in quality. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC), the Department of Justice, and state antitrust agencies each play a role in challenging consolidation and other anticompetitive practices in health care markets. The federal agencies have signaled their interest in expanding their scrutiny of different types of mergers and acquisitions, including cross-market mergers, private equity acquisitions, and vertical consolidation. The extent to which antitrust agencies play an active role and are successful in challenging anticompetitive practices will likely have an effect on health care costs. Some have proposed strengthening antitrust regulation as a tool for tackling rising health care costs, increasing the affordability of care, and reducing the large number of adults with medical debt. Nonetheless, there are challenges to an approach that relies solely on efforts to foster competitive provider markets through antitrust regulation, for example, given the already high level of market concentration of health care providers across the country.